From Analog To Digital in Concert Photography

Thee Oh Sees photo by Ebru Yildiz. Used with permission.

When we look back through photography’s most iconic images of rock n’ roll, the most memorable shots in music history were captured on 35mm black & white film. Fast forward to today’s primarily digital world, photographers are able to produce images in both black & white and color, without the extra steps of processing film rolls through messy chemicals to create a negative. Photos can now be uploaded from a digital camera with immediate viewing to a wide audience. This advancement in technology has allowed basically anyone to capture images at concerts, blurring the line between photographer and music fan. But has this shift to digital altered the essence of the images created from the live music experience? As a concert photographer myself, I spoke with a couple of current seasoned music photographers who began their careers using analog film, on how the progression from film to digital effects the images they create in the live music scene.

The Strokes photo by Ebru Yildiz. Used with permission.

Say what you will about the debate on film versus digital, but this discussion is specific to live concert photography. Yes, medium format film cameras have a distinctly authentic look that digital cannot emulate, similar to how a vinyl recording will have a much richer, organic sound than a mp3. I’m only talking about rock n’ roll here–dark venue stages, unpredictable lighting, guitar players thrashing around and singers jumping into a crowded room of sweaty music fans pressed against the stage’s edge. No quiet portraits in natural lighting, but one of the hardest situations to shoot film in – live music, which is next to impossible to do with medium format. While photography greats such as Annie Leibovitz and Mick Rock shot black & white film in the 1970’s as that was the only option, we now can choose from a vintage film camera and any digital gear you can afford. We can shoot in color, deciding afterward to convert to black and white using software to create a new look. Or just point your smart phone with one hand, beer in the other, and post your shot to Instagram while the band is still playing.

I used to tell myself that learning photography over 20 years ago on an old 35mm film camera, then developing the negatives in my bathroom, has made me a better photographer than I would be starting with a 21 megapixel digital. If you haven’t experienced the patience required to roll film on a metal spool in total darkness, knowing a small kink can result in permanent disaster, I suggest you experience the sweat this induces at least once. Today I feel that it wasn’t really the analog process, but the amount of time, energy, and tenacity it took to get even one image worth printing on paper, that made me a better photographer. But there is something truly magical about this process that cannot be derived in Photoshop. According to the photographers I spoke with, no digital camera released yet is replicating the authentic look achieved only with actual film.

From “We’ve Come So Far – Last Days of Death By Audio” photo book by Ebru Yildiz. Used with permission.

Brooklyn music photographer has shot plenty of film, which she still uses for portrait work, but now prefers digital to capture her live music images.

“I think the most important thing you learn with film photography is to choose your frames carefully, instead of shooting in [burst] mode.” says Yildiz. Limited to 36 shots on a roll, you choose every shutter click wisely, rather than blasting away in burst mode on a 64BG memory card, hoping to edit them down to a few good shots. This limitation alone makes you a better photographer.

When shooting film, Yildiz would limit herself to one roll per band at a show. Now with digital, she can shoot many more images but still retains the method of “less is more”. While talent is not reliant on gear, technical expertise certainly offers an upper hand; and unless you learn the relationship yo shutter speed, aperture, and ISO completely, no amount of guessing in auto mode will ever provide consistent results. This is the distinction between taking just a photo of a band and making great images that won’t be forgotten in music history.

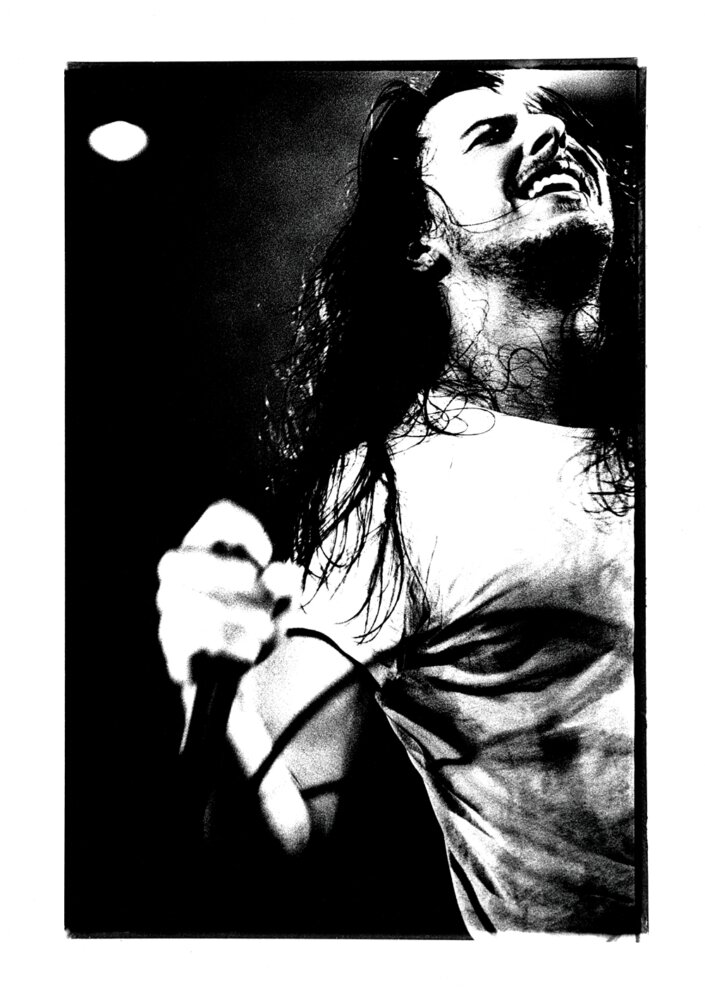

Andrew WK photo by Ami Barwell. Used with permission.

Andrew WK photo by Ami Barwell. Used with permission.

Without the option of on an LCD screen, how do you know you’ve captured solid images with correct exposure at the exact moment the singer was midair using film? Well, you learn your camera settings like the back of your hand, in all manual, so well you can envision the correct aperture and shutter speed with every flashing stage light. Trial and error, and a steep learning curve you climb.

, a UK-based music photographer has been shooting concerts on 35mm film for 20 years, and still never, ever shoots digital.

“Digital cameras are far less accurate and cannot cope with extremely low light and fast-moving conditions; I find digital live music photography painful to look at.”

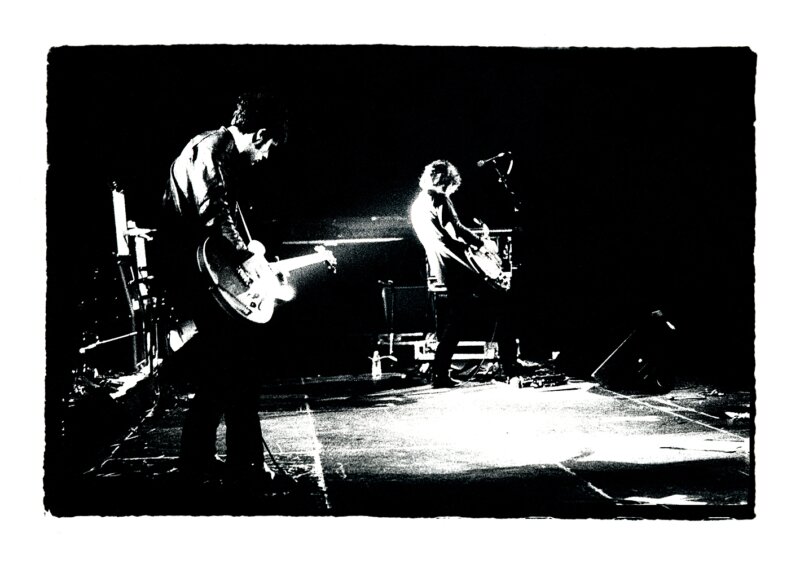

Black Rebel Motorcycle Club photo by Ami Barwell. Used with permission.

Barwell is fast; she can change 7 rolls of films in a dark photo pit during a band’s set, then develop and scan images within 24 hours for publication deadlines. “My turnaround is equally as quick as the majority of digital photographers. So it makes no difference to publications – and they get better quality results on film.” But as Yildiz states, and I find true for me, most publications we work with require a next morning turn around, so upload time need to be less than a few hours. It’s also nice to get some sleep at night.

Both Barwell and Yildiz agree digital cameras are absolutely no match for the look and feel of a true 35mm black and white film photo. Yildiz says people often ask how to get the same “treatment” on her images that inspire them, as in filters or effects, with the biggest inquiry being in her film images. “Funny thing is when I am working on film photos, the only thing I do is increase the contrast, so there is actually no single treatment all!”

So, your Lightroom Black and White Film filter packs are not going to look like you ran Tri-X 400 through developer, it will look like your laptop generated what it thinks is the look of film.

Black Rebel Motorcycle Club photo by Ami Barwell. Used with permission.

A digital image can often look grossly over-processed, and no amount of adjusting in post can correct for a terribly exposed image. Film seems to be a bit more forgiving to imperfect exposure or extreme highlights and shadows from stage lighting. Often times it’s the absence of perfect digital tones and smoothness that gives film it’s uniquely raw look- which is an advantage to a music photographer striving to stand out among the masses of cameras in a photo pit these days. Yet, the higher ISO offered with digital cameras allows shooting the movements of a band in almost total darkness. In Yildiz’s words,“Higher ISO is the single most important advantage with digital cameras. You can make photos without flash, and that is pretty crucial for me.”

I still haven’t decided yet to switch back to film. But as said by rock photography legend Jim Marshall, armed with an old Leica M3, “Its never been just a job, its been my life.” Coming from the only photographer permitted backstage to shoot The Beatles final concert, its clear that dedication was the reason he’s created iconic images of the greatest musicians of all time, not because of the latest gear or luck. Whether using film or digital, always experiment, embrace the struggle, and never do anything in auto. There has never been one great band that played their instruments in auto mode.