Street Photography and Kodak Tri-X Film: 62 Years of Going With The Grain

In recent years, thanks in part to social media and the ease with which participants can share images, street photography has enjoyed unprecedented popularity. A generation of digital cameras, inspired in part by the classic tools of street shooters, has combined with the power of social networks and easy image sharing to empower a new generation of photographers to embrace street photography. The results: A glut of photos: many of them mediocre, some good, and some of them really good.

But even the best of digital street photos have a problem. Digital street photos are too smooth. They’re too clean. They seem clinical. They have very little noise, and certainly no grain. That grittiness, dirtiness that reflects the chaos of the street is missing. And so, software tricks are employed to emulate the graininess of classic films. Click a button, and your grainless digital image suddenly looks like it was shot with the film of choice for many street photographers throughout the years: Kodak Tri-X.

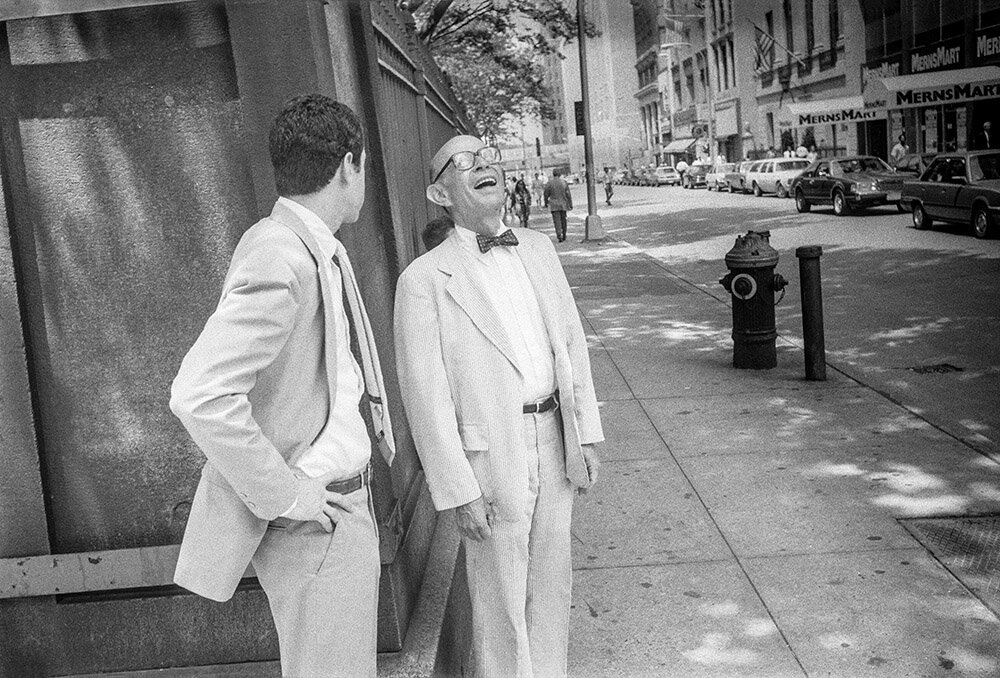

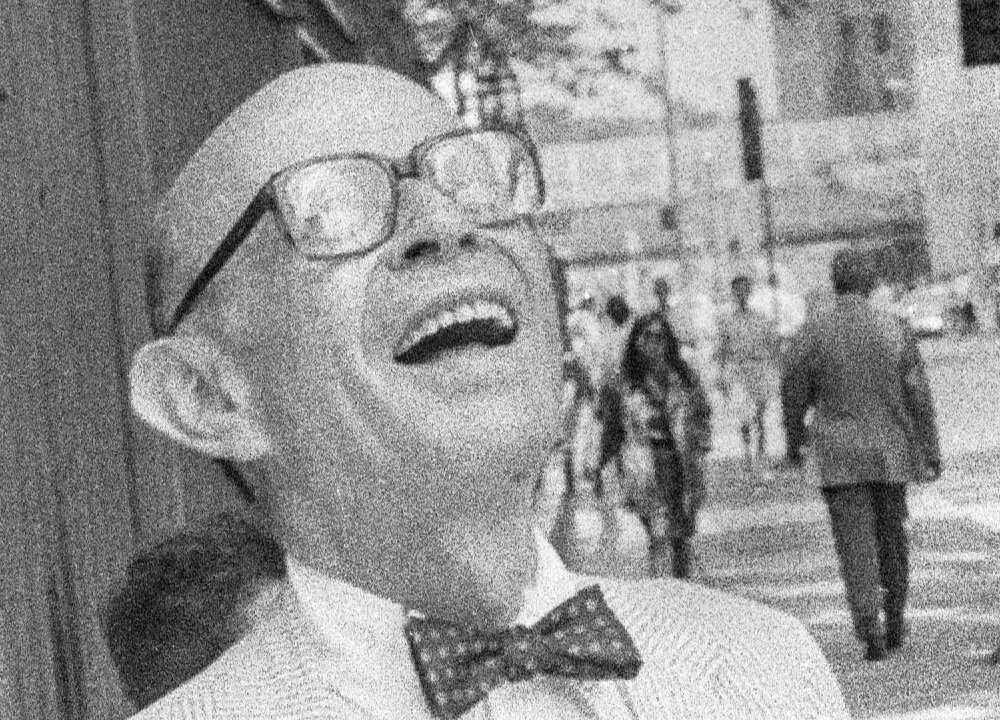

As Bruce Gilden (a Tri-X user) has said, “If you can smell the street by looking at the photo, it’s a street photograph.” Up close, the grain gives the image a pointillist look—something that becomes more apparent the more you enlarge the image. Enlarged, photos shot on Tri-X tend to have a dramatic, gritty feel to them.

The Tri-X look: Photographed by the author in 1976, this photo was shot on Tri-X during a street photography workshop with Garry Winogrand.

Feel the grain: A 100% closeup reveals the gritty grain structure.

A Quick History of Tri-X

Kodak rolled out Tri-X on November 1, 1954 in 35mm and 120 roll film sizes. At ASA 200 (160 for Tungsten), it was faster than any other film available. It changed where photographers could take their cameras and what they could shoot—much like today’s super-high ISO pro-oriented cameras with sensitivities in the ISO 52,000-and-up range are changing how contemporary photographers are approaching low-light photography.

The Tri-X formula underwent one major modification in 1960, when its sensitivity was doubled to ASA 400 for daylight and 320 for tungsten. Now more than ever, low-light situations and action and motion could be captured with outstanding results. “The formula has undergone minor modifications since then, driven by any necessary Health and Safety regulations,” Kodak spokesperson Audrey Jonckheer told La Noir Image. Component material such as gel types and vendor changes, as well as minor changes made to facilitate coating in Kodak’s Building 38, were also made over time.

Image by

But today, Tri-X is basically the same film that was reformulated and introduced in 1960. Paired with D-76, the a film developer that was launched in 1927 and is Kodak’s best-selling black-and-white film developer of all time, it remains the image capture medium of choice for a surprising number of street photographers to this day.

Clinically clean: A recent digital street photo, shot with a Leica M Typ 240 and 28mm Summicron lens. Is digital not gritty enough for the street? Some think so. Photo by the author.

Emulating Tri-X: The same photo, with Silver Efex’s Tri-X setting applied. It’s grainier and higher in contrast, and gives the photo a similar “bite” to Tri-X.

The Tri-X Look

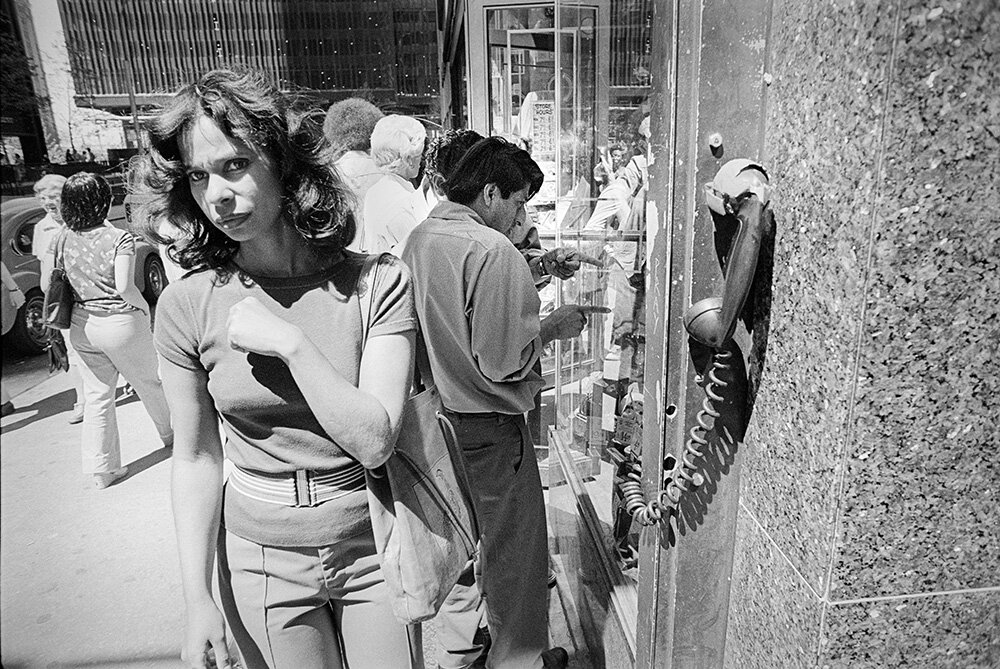

There are both artistic and technical reasons why street photographers over the last 60-plus years have embraced Tri-X. Its graininess, contrast and exposure latitude may be aesthetically pleasing if you’re trying to get that gritty, street-smart look–but those features also serve a practical purpose, covering up a multitude of sins that are inevitable in the chaotically uneven, uncontrolled lighting and shooting situations that come up on the street.

Tri-X is said to have a wider than usual exposure latitude for a black-and-white film (anywhere from 5-7 stops, depending on who your source is). For street photographers who deal with open shade, direct sunlight, cloudy skies and streetlight illumination as well as flash, and often have to make split-second decisions regarding exposure and when to press the shutter release, this has been a godsend. Tri-X can be underexposed by three stops and you can still get a good exposure with push processing, according to Kodak’s technical data for the film. At ISO 1600, this ISO 400 film can produce outstanding, if somewhat grainy, images.

Street Photographers and Tri-X

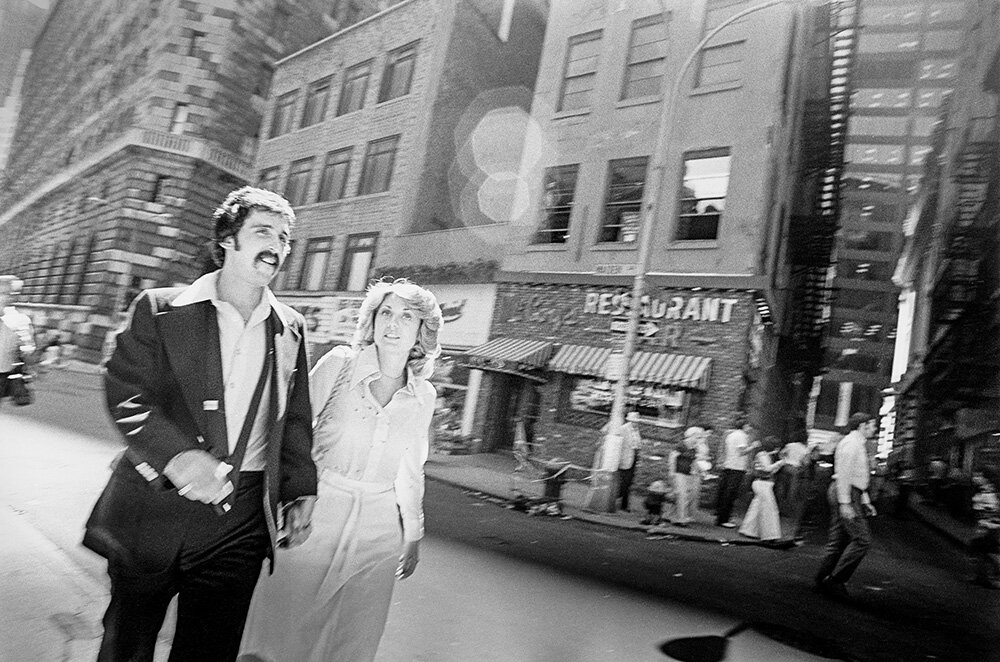

A case study of how one street shooter used Tri-X was Garry Winogrand, whose street photography in the 1960s and 70s influenced a generation of street photographers. Mr. Winogrand primarily used Tri-X, a Leica M camera, and a 28mm lens–a setup that many street photographers have emulated. Each roll of film he shot had a strip of masking tape on which he jotted down the exposure and shooting conditions, and a note about whether the film needed to be push- or pull-processed.

Mr. Winogrand developed the film by inspection, holding it up to a weak green light in the darkroom in the middle of processing to gauge how much longer it needed. Since months or even years would go by between the moment Mr. Winogrand pressed the shutter and when he would process the film, the written reminders were an essential part of his unusual workflow. Given the often chaotic nature of his subject matter, it may be surprising to some that he exerted that level of control over the development process. While he occasionally switched to Plus-X, he preferred Tri-X, which he bought in 100-foot rolls and bulk loaded to save money.

Tri-X is said to have a wider than usual exposure latitude for a black-and-white film (anywhere from 5-7 stops, depending on who your source is).

Henri Cartier-Bresson switched to Tri-X in the mid-50s, embracing its faster emulsion (ASA 200 at the time) for his groundbreaking decisive moments. Magnum photographer Bruce Davidson chose Tri-X when he shot black-and-white images such as his classic photos documenting the civil rights movement in the 1960s, and the film added to the grit of his two-year-long documentary of families struggling to survive on East 110th Street in Harlem. Likewise, fellow magnum photographer Bruce Gilden primarily prefers Tri-X for his high-impact, flash-illuminated head-on shots taken on the streets of Manhattan, Coney Island and elsewhere.

British street photographer Tony Ray-Jones went back and forth between his two favorite ASA 400 emulsions, Tri-X and Ilford HP-5 during his all-too-brief career. Josef Koudelka famously photographed gypsies in 1960s Europe with Tri-X. Sebastiao Salgado wouldn’t switch to digital until he was able develop a digital post-production workflow that could consistently emulate the same gritty look that he got from his beloved Tri-X. Robert Frank used Tri-X for many of the photos that would appear in his seminal 1958 book, The Americans. Vivian Maier, whose recently-discovered, posthumously-publicized images are now considered among the most important street photos of the 20th century, shot Tri-X in 35mm and 120 format. Elliott Erwitt, who brought a strong sense of visual humor to his street photography, also used…you guessed it…Tri-X.

Who’ll stop the grain?

Does the street photographer’s love affair with Tri-X continue in the digital era? A growing number are rediscovering it after being disappointed by the squeaky-clean look of digital. After 62 years, it is still going strong.

All photos in this post are by the author, shot under the watchful tutelage of Garry Winogrand in New York 1976.